Maritime Silk Road

Trade Networks

How Óc Eo connected the Roman Empire, India, Persia, and China through maritime commerce

Gateway of Maritime Commerce

Óc Eo occupied a strategic position on the maritime trade route connecting the Mediterranean world with China. As the principal port of the Funan Kingdom, it served as a crucial transshipment point where goods from the West were transferred to vessels sailing to China, and vice versa.

The Liang Shu records that Funan was "more than 3,000 li from the Linyi [Champa] border" and that merchants "of various kingdoms beyond the frontier" traded there regularly. Archaeological evidence confirms this cosmopolitan nature—artifacts from Rome, India, Persia, and China have all been recovered from the site.

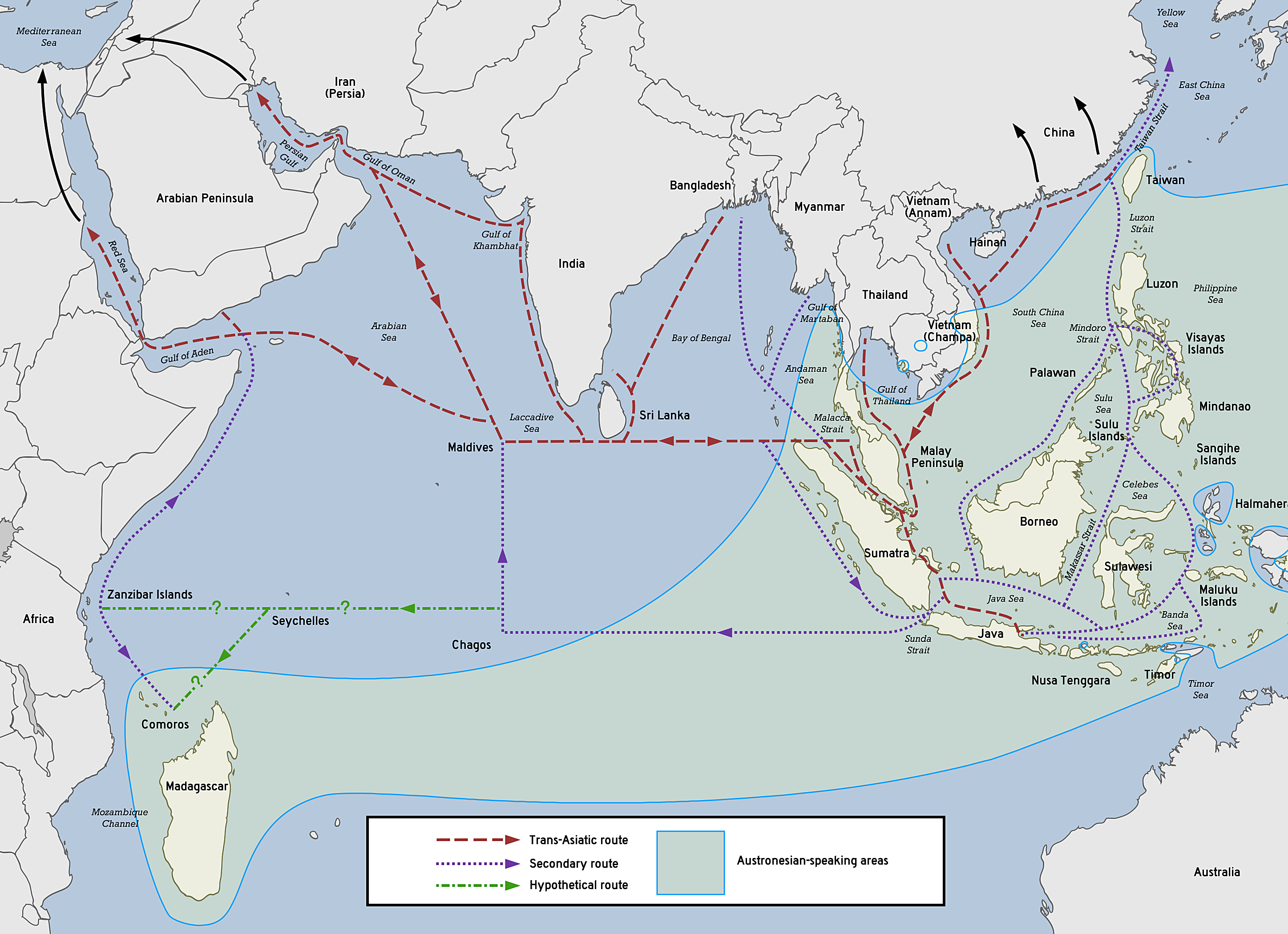

Austronesian Maritime Trade Network

Óc Eo was part of a vast maritime network spanning the Indian Ocean

Proto-historic and historic maritime trade network showing the extent of Austronesian and Maritime Silk Road connections

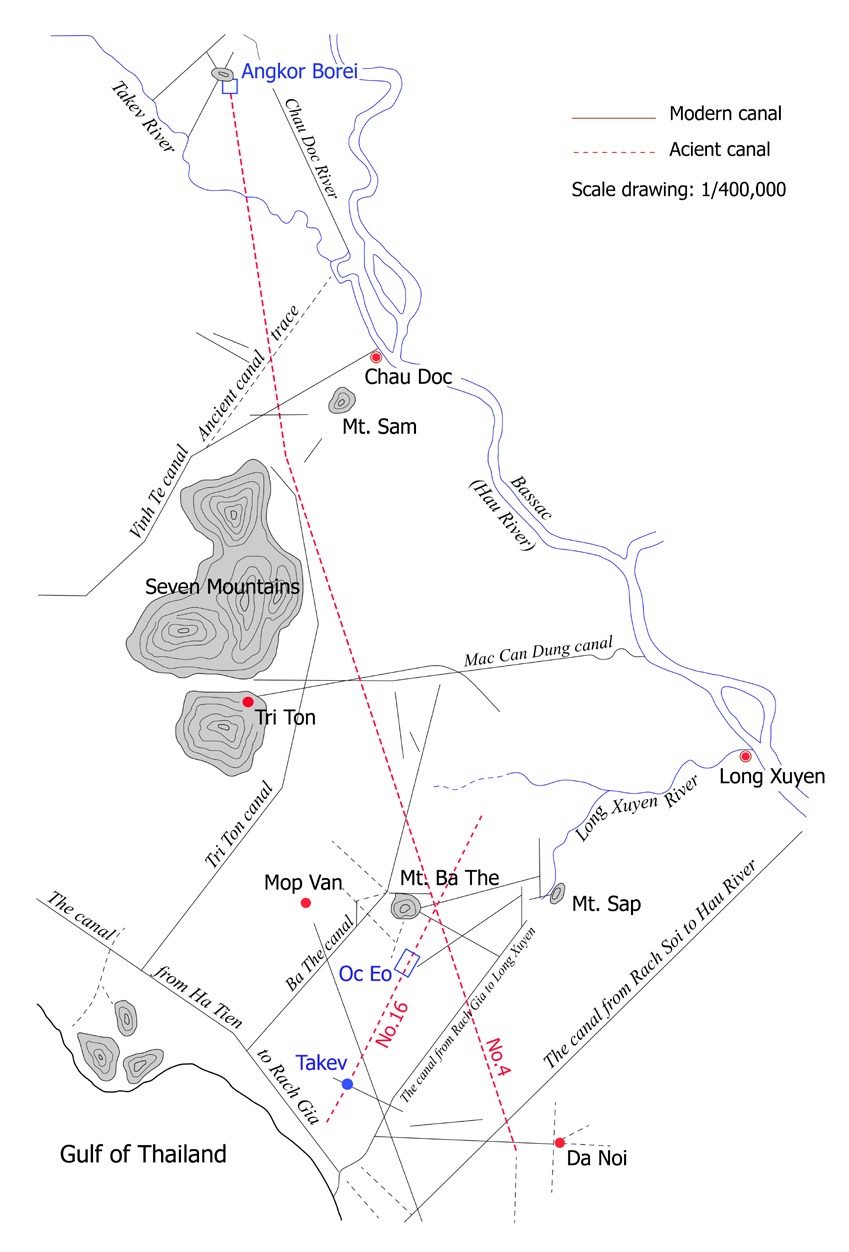

Ancient canal network connecting Óc Eo to Angkor Borei - Nguyen (2023)

Major Trade Routes

Four primary corridors connected Óc Eo to the ancient world

Western Route (Roman Empire)

Goods traveled from Alexandria through the Red Sea, across the Indian Ocean via monsoon winds to Indian ports, then onward to Southeast Asia.

Key Goods:

- • Gold medallions and coins

- • Glass vessels and beads

- • Precious metals

Indian Route

Direct maritime connections with ports on India's eastern coast, particularly the Coromandel region and the Ganges Delta.

Key Goods:

- • Religious statuary

- • Cotton textiles

- • Semi-precious stones

Persian Gulf Route

Connections with Sasanian Persia via the Persian Gulf and Arabian Sea, often through Indian intermediary ports.

Key Goods:

- • Glass beads

- • Metalwork

- • Textiles

Chinese Route

Coastal route northward through the South China Sea to ports in southern China, particularly Jiaozhi (northern Vietnam) and beyond.

Key Goods:

- • Silk fabrics

- • Bronze mirrors

- • Ceramics

Traded Commodities

Funan Exports

Gold

Abundant local sources mentioned in Chinese records

Aromatic woods

Eaglewood (agarwood), sandalwood

Ivory

From local elephant populations

Kingfisher feathers

Highly valued in Chinese court

Spices

Cardamom, cloves, and other aromatics

Pearls

From coastal fisheries

Funan Imports

Silk

Chinese silk for local use and re-export

Bronze mirrors

Han and later dynasty manufacture

Ceramics

Chinese stoneware and porcelain

Glass beads

Roman, Indian, and Persian origins

Religious objects

Indian Buddhist and Hindu statuary

Wine & olive oil

Mediterranean products

Archaeological Evidence

Imported Artifacts

Roman coins, Chinese mirrors, pottery - Nguyen (2023)

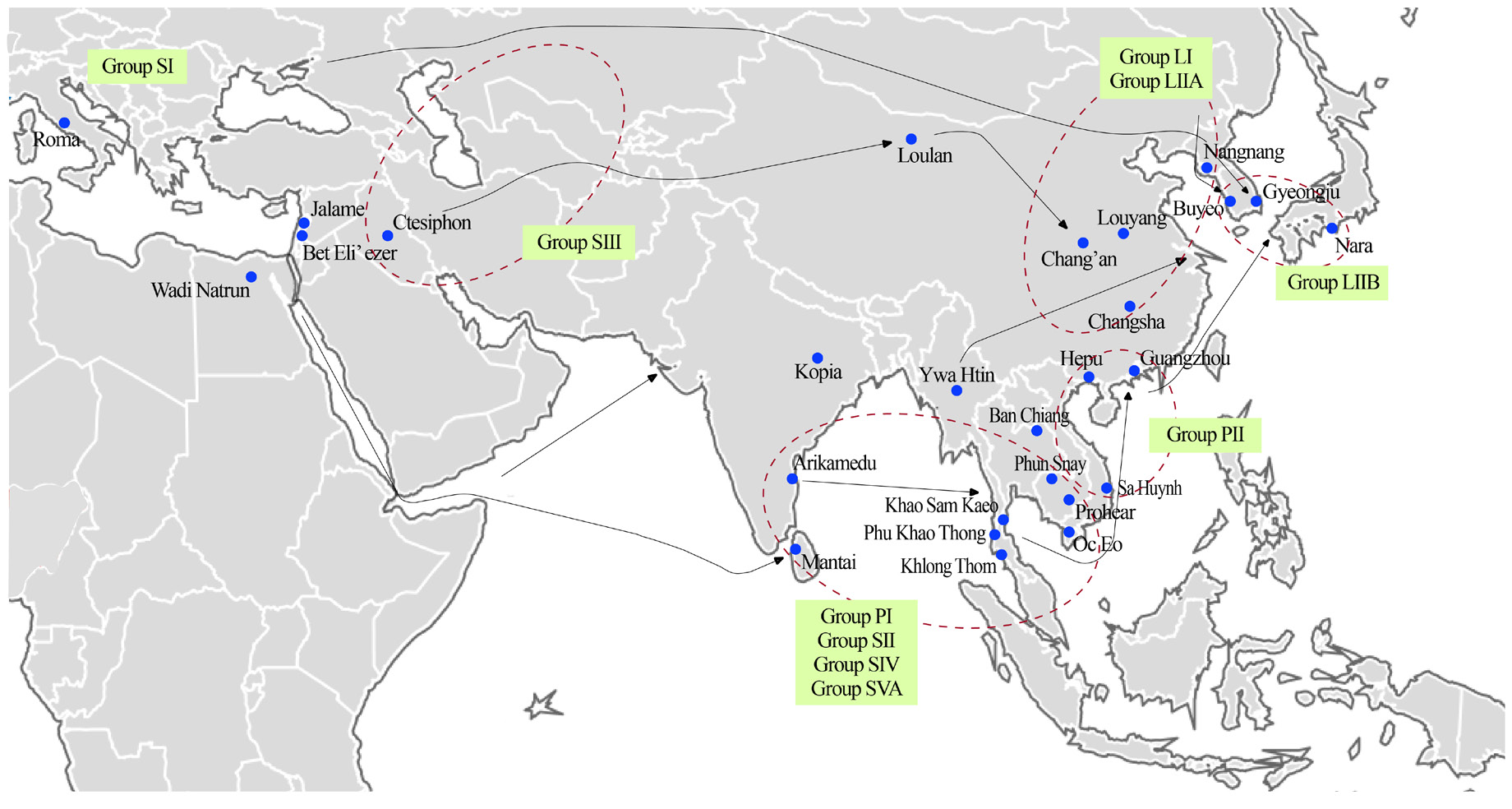

Glass Bead Trade Routes

Provenance analysis - Nguyen (2023)

Source Evidence for Trade

Liang Shu on Commerce

"There are walled cities, palaces, and houses. The men are ugly and black, with curly hair. They go about naked and barefoot... The people devote themselves to agriculture. They sow one year and reap for three. They are fond of engraving ornaments and of chiseling. Many of their vessels for eating and drinking are made of silver. Taxes are paid in gold, silver, pearls, and perfumes."

This passage reveals a sophisticated economy with precious metal taxation and skilled craftwork.

Kang Tai's Account (~250 CE)

"The people of Funan are cunning and shrewd; they attack and subjugate the neighboring kingdoms, which all acknowledge themselves vassals... Merchants from India frequently come to trade."

The Wu diplomat's account confirms regular Indian merchant presence and Funan's regional dominance.

Periplus Maris Erythraei (~40-70 CE)

"Beyond this region, by now at the northernmost point, where the sea ends somewhere on the outer fringe, there is a very great inland city called Thina from which silk floss, yarn, and cloth are shipped by land..."

The anonymous Greek merchant's guide describes the eastern terminus of maritime trade routes, likely referring to the region including Funan.

166 CE Embassy

The Roman Connection

Chinese records in the Hou Han Shu document that in 166 CE, envoys claiming to represent "Andun" (Marcus Aurelius Antoninus) arrived at the Chinese court via Rinan (central Vietnam), bringing gifts of ivory, rhinoceros horn, and tortoise shell.

While scholars debate whether these were official Roman envoys or private merchants, the episode demonstrates that maritime routes from the Mediterranean to China via Southeast Asia were well-established by the 2nd century CE.

Archaeological confirmation: The golden medallions of Antoninus Pius (138-161 CE) and Marcus Aurelius (161-180 CE) found at Óc Eo provide tangible evidence of Roman goods reaching Southeast Asia during this period.

15th century reconstruction of Ptolemy's world map - Kattigara appears at the eastern edge of the known world

Ships & Navigation

The Liang Shu provides valuable details about Funanese maritime technology:

"The people take boats to engage in trade; they can make boats more than 80 feet long and 6 feet wide. The bow and stern are like the head and tail of a fish."

8th century Borobudur relief depicting an outrigger trading vessel similar to those used in Funanese maritime commerce

Large ocean-going vessels

Narrow beam for speed

Distinctive bow and stern

Monsoon Navigation

Trade across the Indian Ocean depended on the monsoon wind system. Ships from India would depart during the northeast monsoon (November-February) and return with the southwest monsoon (May-September). This seasonal rhythm shaped the commercial calendar of all ports along the Maritime Silk Road.

Economic Significance

Transshipment Hub

Óc Eo's location at the isthmus point meant goods were often transferred between vessels rather than making the longer voyage around the Malay Peninsula. This generated significant revenue through port fees and services.

Local Manufacturing

Evidence of local gold jewelry production imitating Roman coins and minting of silver coins with the hamsa bird suggests Óc Eo was not merely a transit point but also a manufacturing center.